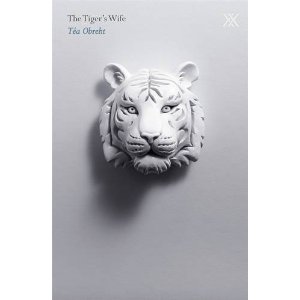

From the book cover

From the book coverIn contemporary Sierra Leone, a devastating civil was has left an eerie populace with terrible secrets to keep. In the capital hospital, Kai, a gifted young surgeon, is plagued by demons that are beginning to threaten his livelihood. Elsewhere in the hospital lies Elias Cole, a man who was young during the country's turbulent post-colonial years and has stories to tell that are far from heroic. As past and present intersect in the buzzing city, Kai and Elias are drawn unwittingly closer to Adrian, a British psychologist with good intentions, and into the path of one woman at the center of their stories.

The book gets its name from Kai's feelings for ex-girlfriend, Nenemah/Mamakey.

The hollowness in his chest, the tense yearning, the loneliness he braces against every morning until he can immerse himself in work and forget. Not love. Something else, something with a power that endures. Not love, but a memory of love. p. 185

One of the reasons I'm disappointed that I can't add this book to my 5ers list is the many strong lines and passages. Here are a few of my favourite lines/passages from the novel:

This first line is spoken by a native Sierra Leone psychiatrist (Dr. Attila) during a conversation with Adrian regarding Adrian proposed treatment plan for some of the resident of the mental hospital he manages:

'This is their reality. And who is going to come and give the people who live here therapy to cope with this?' asks Attila and waves a hand at the view. 'You call it a disorder, my friend. We call it life.' p. 319

Adrian after Mamakey dies during childbirth:

He knows what he is doing. He's already bartering with God, making offerings. It is for just such times that humankind invented gods, while hope still exists. When hope disappears, men don't call for God, they call for their mothers. p. 419

Adrian two years after Mamakey's death:

Adrian cannot believe with what intensity one can continue to love a person who is dead. Only fools, he believes, think that love is for the living. p. 439

Shortly after this last excerpt, we find out that Kai is raising Adrian and Mamakey's daughter - the one she died giving birth to! If Adrian loves her so much, wouldn't he want to raise their child? This development was unreal for three reasons:

1) Why would Kai want to raise his ex-girlfriend's child with another man. I get that she's the love of his life, but it still doesn't add up.

2) Given the great love that Adrian is suppose to feel for Mamakey why would he consent to another man raising their child?

3) Adrian expresses so much remorse at not having convinced Mamakey to leave Sierra Leone, why would he then leave their child there?

On to the characters...

I know I said earlier that the character are dynamic, let me clarify. Aminata Forna has done a fabulous job of creating characters that jump off the pages, part of what makes them so real is the fact that they are not all likable. Kai is the only main character that I can stomach. Elias Cole and Adrian appear to be the same character in different circumstances. They are both jealous, selfish and fickle.

Elias covets his friend's wife, only to embark on a long term affair once he is married to her. Worse yet, he's an opportunistic coward, who always shifts responsibility for his actions onto the establishment or someone else.

Adrian is remarkably slow for a psychologist, he fails to make a lot of obvious connections. It's hard to believe he is trained to decipher people's feelings and read between their emotional lines. Also, his selfish disregard for the wife and daughter he left in England is shameful. Adrian's sole redeeming quality is his ability to listen to victims and villains and remain non-judgemental.

This lack of judgement is one of the reason's I so yearn to put

The Memory of Love on my 5ers list. Aminata Forna refrains from preaching, lecturing or judging as she shares the stories of the men who committed atrocities, and the women and men who suffered through the atrocities. She allows us see the human side of these 'villians.'

I will definitely be reading

The Memory of Love again. If you have not read it, I highly suggested you read it. It's one of the most meaningful books I have read to date.

4.5/5

Room by Emma Donaghue made it onto my 5ers list, and thus is the novel I think should have won the 2011 Orange Prize. Room was really easy to get into and very relevant with all of its similarities to the various high-profile cases that have made international news in the last couple of year. Donaghue's decision to tell the story in the voice of a very smart five-year-old boy is genius. It made all the difference in what would otherwise have been a very depressing story.

Room by Emma Donaghue made it onto my 5ers list, and thus is the novel I think should have won the 2011 Orange Prize. Room was really easy to get into and very relevant with all of its similarities to the various high-profile cases that have made international news in the last couple of year. Donaghue's decision to tell the story in the voice of a very smart five-year-old boy is genius. It made all the difference in what would otherwise have been a very depressing story.